Welcome to a new direction for the “Road to Know Where”. My pursuit of documenting the ongoing nooks & crannies of Microsoft’s Windows and Office has taken a back-seat to my other passion: Musical Improvisation and Jazz Harmony.

I’ve been (re)studying and performing at two local colleges and continually struck with a few BIG misunderstandings among my fellow students (and some teachers). I’ll be posting detailed information on these topics – but I wanted to get the conversation going:

Thinking “Playing by ear” is a bad thing is wrong! – Most people apologize when admitting they only “play by ear”. As children we learn to speak by imitating the speech we hear (aka “playing by ear”). Later we learn how to read and write our native language. It’d be great if all music students began by “playing by ear” then learned how to read and write music. Similarly to being able to read a book, or write a letter – without learning how to read and write music you are musically illiterate. That sounds harsh, but the musical world opens-up when you learn to read music. It’s also important to express yourself by creating and improvising your own music.

Having “perfect pitch” would make me a better musician, yes however… – There’s no question having “perfect pitch” would be immensely helpful. However you should already be “playing by ear” (see previous). You can later be trained to have “relative pitch”.

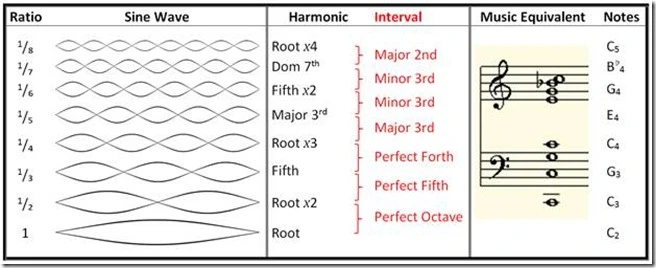

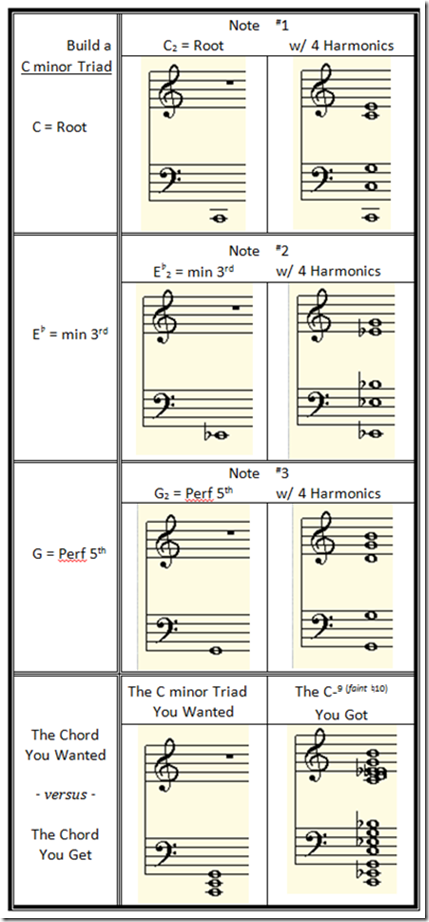

Why do we learn the Circle of 4th and 5th? – Most music students (and some teachers) do not study the technical history of Western Music, or science of sound (aka Acoustics). This is understandable; to become a great Bread Baker you needed know the ancient history of yeast. However, knowing the science behind harmonic overtones and history behind Pythagoras’ Circle of 5th are crucial to truly understanding the construction and movement of chords.

Jazz Harmony is different than Traditional Harmony – I hear students say they don’t need traditional harmony, because they’re going to study Jazz/Rock harmony.

NO – Our Western Harmony has a 2000+ year old history that evolved alongside the development of our alphabets, languages, religions, calendars, mythology and sciences. Jazz Harmony is nothing more than a very minor extension of Traditional Harmony.

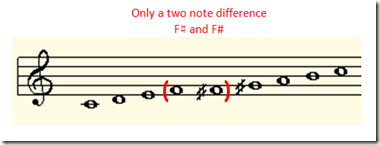

YES – There are some differences between Jazz Harmony and Traditional Harmony. However, they are very minor yet still seem to be a point of contention.

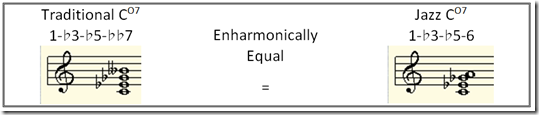

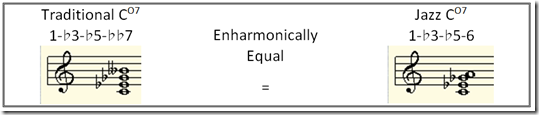

Jazz has no double-sharps or double-flats – Not sure if Jazz musicians were being lazy or simplifying the reading of music; however double-sharps and double-flats are converted to their “easier to read” enharmonic. Example: A traditional diminished chord consists of 1-b3-b5-bb7 however in Jazz the double-flat seventh would be written as a sixth 1-b3-b5-6

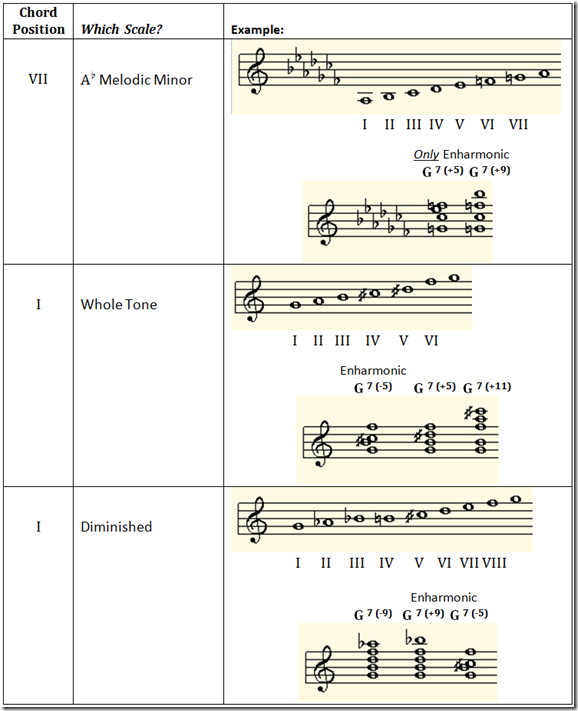

Jazz Uses “Enharmonic” Chords – Example: There is no G7-5 or G7+5 in the Ab Melodic Minor scale. However, enharmonically there are – so in Jazz we’ll play the Ab Melodic Minor scales against either the G7-5 or G7+5 chords (as well as a standard G7).

Jazz Rhythm is not “strict” – Yep, that’s true. Example: Eighth notes are not played straight they are “swung”. You’ll see books trying to explain eighth notes either as a form of triplet or using a 12/8 time signature. Both are close approximations to explain swing – however swing is something that needs to be learned by doing (not reading). Kinda like trying to learn to drive a car by reading a book.

Improvising is not only a “Jazz” thing – Throughout human history all musicians have improvised portions of their music. There are Biblical references to music, and Jewish Cantors became some of our first organized musical improvisers. Early musicians improvised against a cantus firmus (“fixed song”) – followed by many years of composers writing “Variations on a Theme”. Most historic musicians and composers were also known for their improvisation:

- Bach (1685-1750)

- Handel (1685-1759)

- Mozart (1756-1791)

- Beethoven (1770-1827)

- Schubert (1797-1828)

- Chopin (1810-1849)

- Shumann (1810-1856)

- Liszt (1811-1886)

- Debussy (1862-1918)

Silent movies were accompanied by improvised piano – so no, improvisation is not a recent Jazz thing.

Chord Voicings – This can be confusing because some chord voicings have omitted notes that “seem” to be needed.

Example: There is no “G” in this common left handed G7 chord voicing of F + B + E – Traditional Harmony and science explains a great deal of how to voice chords, however Jazz adds an enharmonic element (see above). This will make more sense in future postings.

Chord Substitution – Similar to the confusion on Chord Voicing (see previous), Traditional Harmony and science explains a great deal of how to substitute chords, however Jazz adds an enharmonic element (see above). This will make more sense in future postings.

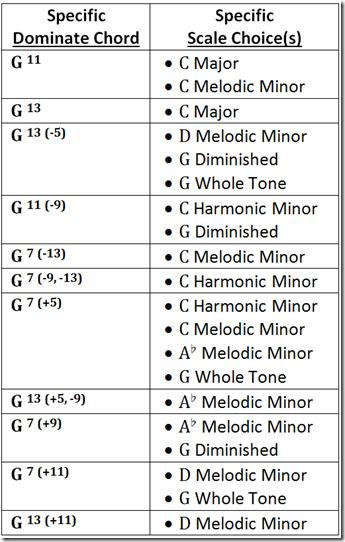

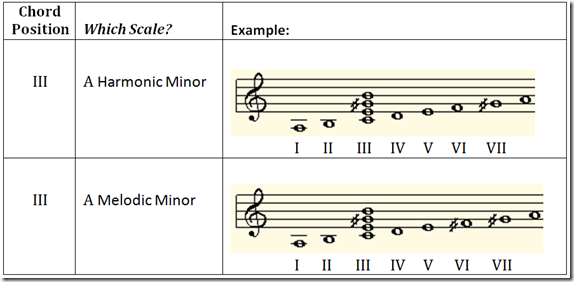

Which scale goes with which chord? – Similar to the confusion on Chord Voicing & Substitution (see previous), Traditional Harmony and science explains a great deal of which scale goes with chord, however Jazz adds an enharmonic element (see above). This will make more sense in future postings.

Example:

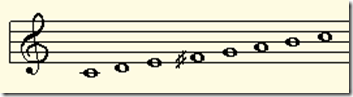

- G7 is IV of D Melodic Minor

- G7 is V of C Major

- G7 is V of C Harmonic Minor

- G7 is V of C Melodic Minor

- G7 is VII (enharmonically) of Ab Melodic Minor

- G7 is I of G Diminished

- G7 is I (enharmonically) of G Whole Tone

Modal Harmony is complicated – Yes it is, and shouldn’t be. Modal harmony began in ancient Greek, who did not call them “modes” nor yet have any types of “scales”. The Greeks had groupings of four “harmonious” tones with local geographic inspired names (i.e. Dorian, Lydian Phrygian). Two pairs of four-tones created eight-note scales, which still retained their modal names. Early Catholic Church “chant” music was written using these scales still with modal names. Many years later those modes were distilled into the two Major and Minor scales we use today. Today, you’re welcome to memorize various names for the modes – however, the names and theory have little to do with today’s music. Just learn to play scales starting from any note, and leave memorizing modal names to Jeopardy contestants.

I’ll never be able to play Giant Steps, Take Five etc. – Not with that attitude! 🙂 There will always (repeat always) be music and musicians beyond your technical capabilities. Great music and musicians should inspire and challange, not frustrate you. Find the style of music you love and simply find easier pieces to master. However, if you wish to improve there’s sincerely no substitute for practice.

I’ll be tackling each of these topics; along with other supplemental lessons to support musicians and students needing the proper tools to understand Jazz Harmony and successfully improvise.

Let the lessons (and your questions) begin!